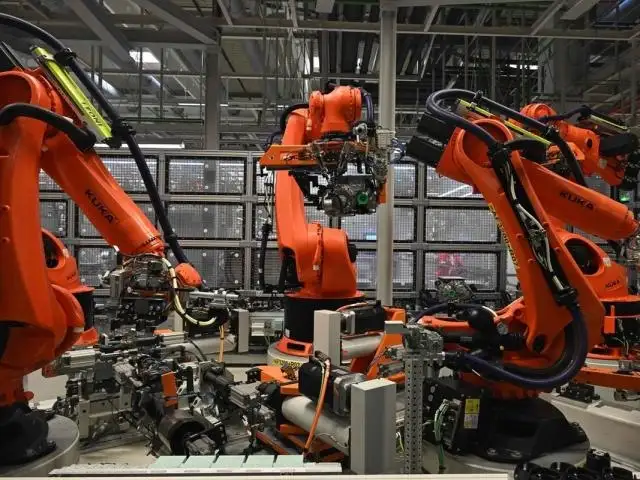

Robots in U.S. factories are facing their own kind of “unemployment” as businesses scale back on automation due to hefty maintenance costs and slowing orders.

Executives across the U.S. are reporting a drop in demand for manufacturing robots. After the COVID-19 pandemic, when labor shortages and rising wages made robots a go-to solution, things are different now. The job market has bounced back, but economic challenges have led to a decline in orders, leaving many robots idle and collecting dust.

According to the Association for Advancing Automation (AAA), robot orders in North American factories in 2023 dropped by nearly a third compared to the previous year, and the downward trend has continued through the first half of this year.

Paul Marcovecchio, an executive at Kawasaki Robotics, which supplies robots to the auto industry, commented, “Factories were rushing to buy robots, fearing labor shortages. Now, they’re realizing they don’t need as many.”

On paper, robots seem like the perfect solution for physically demanding, repetitive tasks. They don’t need breaks, won’t demand a raise, and won’t get hurt on the job. However, Jack Schron, president of Jergens Inc., a U.S.-based component manufacturer, explains that companies often overlook the long-term costs. Maintenance, programming for complex tasks, and other expenses can quickly add up. Many factories that invested heavily in robots after the pandemic are now realizing that automation isn’t always the flawless solution they imagined.

“Automation in manufacturing isn’t disappearing, but it’s definitely slowing down,” Schron added.

Another challenge robots face is the resurgence of labor strikes. Workers, feeling threatened by automation, have pushed back, demanding higher wages and job security. This pressure has eroded the demand for robots in factories.

Economic uncertainty has also made businesses more cautious with investments. High interest rates and weak market demand mean companies are more hesitant to invest in robots, knowing it could take longer to see a return.

Take Athena Manufacturing, based in Austin, Texas, for example. The company purchased seven robots between 2021 and 2022 to keep up with labor shortages in the semiconductor, aerospace, and energy sectors. However, as production dropped by 20% in 2022, Athena has only bought one robot this year. John Newman, Athena’s director, said, “We still use robots, but nowhere near as much as during the height of COVID-19 and the post-pandemic surge.”

While finding skilled labor remains a challenge, reduced market demand means factories aren’t hiring at the same levels they once did. Data from the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, provided by Michigan State University professor Jason Miller, shows that only 21% of manufacturers cited labor shortages as a barrier to full production in the second quarter of 2024—down from 45% in the same period in 2022. This shift has further lessened the need for robots to fill labor gaps.

The automotive industry, traditionally the largest user of robots in North America, has seen a 20% drop in robot orders in the second quarter of 2024, according to AAA. The slowdown in electric vehicle (EV) production has contributed to this decline, leaving many robots “unemployed.”

Bill Adler, president of Stripmatic Products, had plans to automate laser welding for EV frames. However, with EV orders down to just a quarter of the expected volume, he’s opted to hire human workers instead, making large investments in automation seem impractical.

Scott Marsic, an executive at Epson Robots, noted, “EVs were hot when they first hit the market, but now the buzz has cooled, and robot sales have dipped along with it.” Marsic remains hopeful, however, that the demand for robots could rebound once interest rates in the U.S. fall, making these machines more affordable.

For now, though, many robots are left waiting on the factory floor, as businesses re-evaluate the true cost of automation.